Blocked Salivary Glands: Home and Clinical Remedies

Disclaimer

This post is not intended to diagnose, treat, or cure any condition. It is intended for informational purposes only. Consult with your dentist if you have any questions about the status of your mouth.

Salivary Glands 101

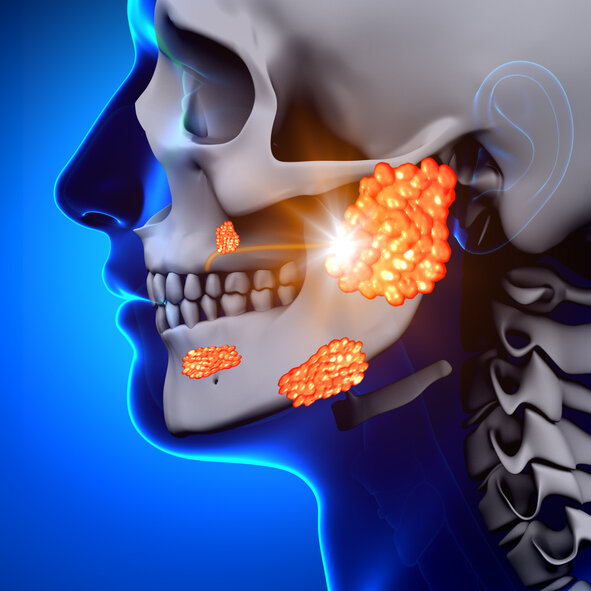

There are three main salivary glands. The glands located on the cheeks are called the parotid salivary glands. The ducts associated with the parotid salivary gland are on the inner cheek adjacent to the molars and are called Stensen’s ducts. The two glands located under the tongue are called the sublingual glands. The multiple ducts associated with the sublingual glands are known as Bartholin’s ducts and the ducts of Rivinus. Finally, there are two glands located bilaterally under the jaw known as the submandibular glands. They discharge into one larger duct situated under the tongue called Wharton’s duct. Additionally, there are hundreds of individual glands located throughout the mouth as well.

Blocked Salivary Glands

Occasionally, the ducts can get clogged, causing unusual pain and swelling. The most common blockages happen on the palate. They appear as small hard bubble-like swellings that come and go; they are self-limiting and of little concern. Another common occurrence is juvenile recurrent parotitis, which is swelling of the parotid glands of the cheeks that happen in young children. There is no known cause, but the bouts usually cease at puberty. The treatment is often palliative.

Salivary Gland Stones

Crystals can form within the saliva that create a nidus for stone formation, known as sialoliths, similar to those in the urinary tract. Like kidney stones, they usually occur on one side only. They can lead to obstruction of the duct with rapid swelling and pain in the gland and, ultimately, infection. (1) 1.2 percent of adults will experience salivary stones. (2) Underlying conditions like Sjogren’s syndrome, being elderly, taking medication that causes dry mouth, head and neck radiation treatment, kidney failure, and head and neck trauma are risk factors for sialoliths. (3)

Occurrence Of Stones

80% of salivary gland stones occur in the submandibular glands, 2% occur in the sublingual glands, the rest take place in the parotid glands. (4) The reasons that submandibular gland stones are so prevalent are that the saliva is more alkaline, thicker, and contains a higher amount of calcium phosphates. Additionally, the duct is long and twisted, and the gland lies below the duct, making stasis (lack of flow) much more common. (5) Diagnosis is typically through clinical and radiographic examination. (6)

Early Treatments For Stones

Once the salivary flow becomes blocked, episodic pain and swelling can result. In the case of a submandibular blockage, swelling under the jaw is experienced. In parotid blockage, swelling of the cheek that looks like mumps will be the norm. The rare cases of sublingual obstruction will present as swelling under the tongue in the floor of the mouth. Initial treatment centers around stimulating salivary flow to clear the blockage. Vitamin C, lemon, and sour candy help to stimulate the flow of saliva. These agents are called sialogogues. The extra flow of saliva can help flush out the stone or other debris blocking the flow. The recommendation to stay well hydrated is never more critical when a salivary blockage is suspected. Warm compresses also help. Lastly, a healthcare professional (usually a dentist or ENT specialist) will attempt to remove the stone by applying gentle pressure to the swollen area. Sometimes physically dilating the canal of the duct is done before attempting to remove the blockage.

Late Stage Treatment For Stones

If the blockage persists, an infection may ensue. Antibiotics help control the infection. The swelling from the infection may help dislodge the stone. If the blockage persists, there are three approaches to consider. The gold standard used to be surgical resection of the duct that usually resulted in the total removal of the gland from complications. Due to the facial nerve location, removal of the parotid gland is hazardous. Facial paralysis is a considerable risk. Luckily sialoliths rarely block the parotid gland. The second method is breaking up the stone via Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL), otherwise known as lithotripsy. ESWL for salivary stones is the exact method used to break up kidney stones. Ultrasonic sound waves directed at the stone cause the break-up of the sialolith into smaller pieces that will freely pass. It is 40-70 percent effective and may take several visits. (7) Unfortunately, this approach has not met approval in the United States.

Finally, there is a new procedure that is far less invasive called sialendoscopy that involves using an endoscope that can fit into the canal of the duct and visualize the stone. Its use is both diagnostic and interventional. It is a minimally invasive outpatient procedure performed under local anesthesia and is 98 percent successful as a diagnostic aid. (8) Once the location of the sialolith is determined, instruments can pass through and grab onto it and pull it out of the duct (see the illustration below). If the stone is too large, breaking it up with a micro-drill or a laser through the scope is an option. Sialendoscopy has an 85 percent success rate that minimizes risks associated with traditional surgical interventions like facial paralysis. (9) Oral surgeons and ENT specialists perform Sialendoscopy, but most often, general dentists diagnose and perform the early interventions. Any facial swelling is an immediate concern, whether it is a blocked salivary gland or not. If you are experiencing any facial swelling, you should have it evaluated immediately.

Stone being removed by sialendoscope with basket tool