Why Your Thyroid Issues Might Start in Your Gut: The Hashimoto’s Connection

Low thyroid function, or hypothyroidism, affects millions worldwide, often leaving individuals grappling with fatigue, weight gain, brain fog, and a host of other symptoms. For many, the root cause lies in autoimmune conditions like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which is closely linked to a lesser-known but critical factor: leaky gut. Pioneering researcher Dr. Alessio Fasano has revolutionized our understanding of how intestinal permeability, or leaky gut, drives autoimmune diseases, including Hashimoto’s. In this post, we’ll explore the prevalence of low thyroid function, the autoimmune mechanisms behind Hashimoto’s, and the role of leaky gut, backed by Fasano’s groundbreaking work.

How Common Is Low Thyroid Function?

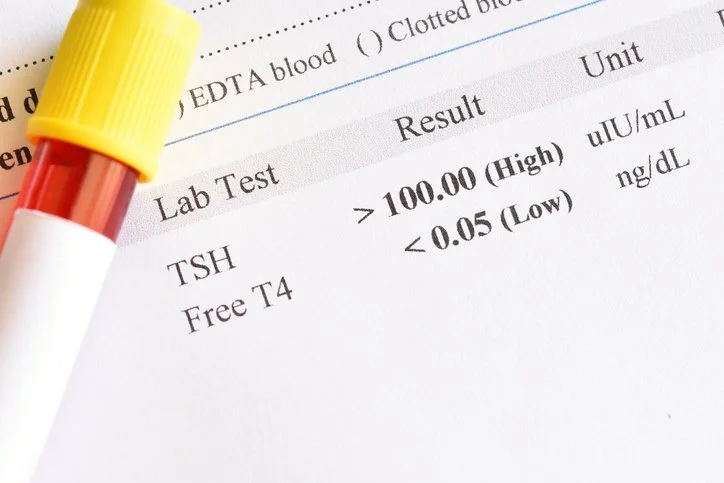

Hypothyroidism is one of the most prevalent endocrine disorders globally. In the United States, it affects approximately 4.6% of the population, with women being significantly more susceptible than men. The condition becomes more common with age, particularly in women over 60, where prevalence can reach up to 10%. Low thyroid function often manifests as insufficient production of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4), which regulate metabolism, energy, and overall bodily functions. Symptoms include fatigue, cold intolerance, weight gain, dry skin, hair loss, and difficulty concentrating, often prompting patients to seek thyroid hormone replacement therapies like Synthroid or levothyroxine.

However, low thyroid function is not always straightforward. Many cases are undiagnosed or misdiagnosed due to subclinical hypothyroidism, where thyroid hormone levels are borderline, but symptoms are present. Studies estimate that subclinical hypothyroidism affects 3-8% of the general population, highlighting the need for better screening and awareness.

Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: The Autoimmune Culprit

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the leading cause of hypothyroidism in developed countries, accounting for 70-80% of cases. This autoimmune disorder occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the thyroid gland, leading to inflammation, tissue damage, and reduced hormone production. Approximately 1-2% of the U.S. population has Hashimoto’s, with women being 10 times more likely to develop it than men. Diagnosis typically occurs between ages 30 and 50, though it can affect individuals of any age.

The prevalence of Hashimoto’s is likely underestimated due to asymptomatic cases or misdiagnosis. Genetic predisposition plays a significant role, with 80% of the risk attributed to genetics, particularly variations in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex and other immune-regulating genes. Environmental triggers, such as stress, infections, iodine excess, or hormonal changes, can activate the autoimmune response in genetically susceptible individuals.

Hashimoto’s is often associated with other autoimmune conditions, a phenomenon known as polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. For example, 10-40% of Hashimoto’s patients also experience gastric disorders, such as autoimmune gastritis, which can impair nutrient absorption and exacerbate symptoms. This overlap underscores the systemic nature of autoimmunity and the need for a holistic approach to treatment.

Leaky Gut: The Hidden Trigger of Autoimmune Disease

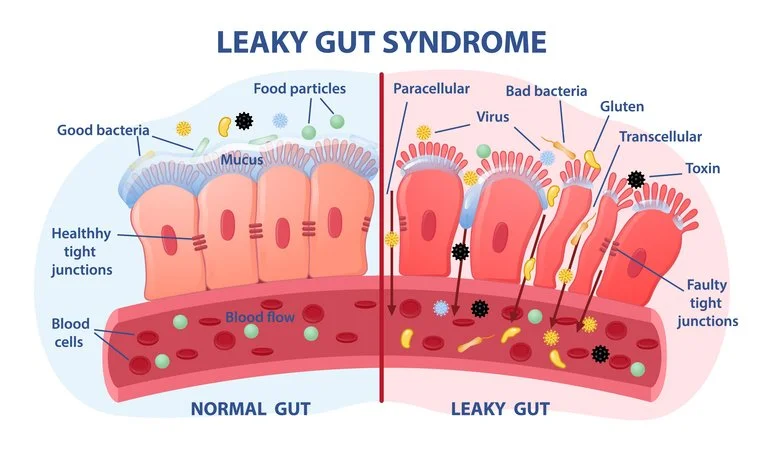

Enter Dr. Alessio Fasano, a world-renowned gastroenterologist whose research has transformed our understanding of autoimmunity. Fasano’s work at the University of Maryland and Harvard Celiac Research Center identified zonulin, a protein that regulates intestinal permeability. When zonulin levels are elevated, the tight junctions in the intestinal wall loosen, allowing undigested food particles, toxins, and bacteria to leak into the bloodstream—a condition known as leaky gut or intestinal permeability. He noted that gluten, the protein found in wheat, rye, and barley, increases gut permeability.

Fasano’s groundbreaking theory posits that leaky gut is a prerequisite for autoimmune diseases, including Hashimoto’s. He describes autoimmunity as a “three-legged stool” requiring:

A genetic predisposition.

An environmental trigger (e.g., gluten, stress, or infections).

Increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut).

Why Your Thyroid Issues Might Start in Your Gut: The Hashimoto’s Connection

In genetically susceptible individuals, leaky gut allows foreign substances to enter the bloodstream, triggering an immune response. Through a process called molecular mimicry, the immune system may mistake thyroid tissue for these foreign invaders, leading to autoimmune attacks. For example, gluten proteins, which are structurally similar to thyroid tissue, can exacerbate Hashimoto’s in up to 20% of patients with autoimmune conditions.

Fasano’s research highlights the role of gluten in driving leaky gut, even in those without celiac disease. In a notable case, Fasano described a colleague’s daughter with Hashimoto’s who, after adopting a gluten-free diet, saw her thyroid antibodies disappear, and TSH levels normalize within three months, which underscores the potential of dietary interventions to reverse autoimmune processes by healing the gut.

The Gut-Thyroid Axis

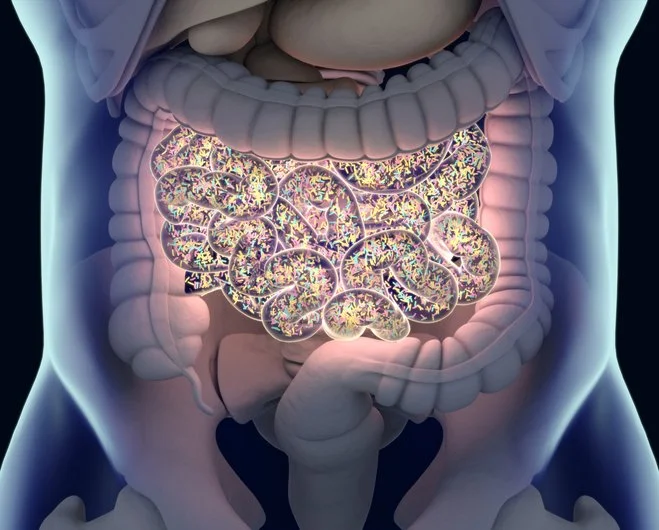

The connection between gut health and thyroid function, often called the gut-thyroid axis, is bidirectional. Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in gut microbiota, can impair nutrient absorption (e.g., iodine, selenium, zinc) critical for thyroid hormone production, worsening hypothyroidism. Conversely, low thyroid function reduces gut motility and bacterial diversity, further promoting dysbiosis and leaky gut. Studies show that Hashimoto’s patients often have reduced beneficial bacteria and higher levels of inflammation-driving bacteria, perpetuating a vicious cycle.

Leaky gut also contributes to systemic inflammation, which can suppress thyroid hormone conversion and increase cortisol levels, further disrupting thyroid function. Common triggers of leaky gut include gluten, stress, food sensitivities, infections (e.g., H. pylori, SIBO), and medications like NSAIDs. Addressing these triggers is crucial for restoring gut integrity and halting autoimmune progression.

Healing Leaky Gut and Managing Hashimoto’s

Fasano’s work emphasizes that re-establishing the intestinal barrier can arrest autoimmune processes. Practical steps include:

Eliminating Triggers: Given its role in zonulin production, a gluten-free diet is a starting point for many. An elimination diet can also identify other food sensitivities.

Healing the Gut: Probiotics, prebiotics, and bone broth can restore gut microbiota and repair the intestinal lining.

Nutrient Support: Ensure adequate intake of selenium, zinc, and vitamin D, which are often deficient in Hashimoto’s patients and critical for thyroid and immune function.

Stress Management: Chronic stress exacerbates leaky gut and autoimmunity, making mindfulness practices essential.

Medical Collaboration: Work with endocrinologists, dietitians, and functional medicine practitioners to monitor thyroid function and adjust levothyroxine dosing.

While thyroid hormone replacement like Synthroid is the standard treatment for hypothyroidism, addressing leaky gut and autoimmunity can reduce reliance on medication and, in some cases, lead to remission. Regular thyroid function tests (TSH, T3, T4, and antibodies) are vital to track progress.

Conclusion

Low thyroid function and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are far more common than many realize, affecting millions and driven by complex autoimmune mechanisms. Dr. Alessio Fasano’s pioneering research on leaky gut has illuminated a critical piece of the puzzle, showing that intestinal permeability is a key driver of autoimmunity. By addressing leaky gut through diet, lifestyle, and targeted interventions, patients can take charge of their health, potentially reversing autoimmune damage and improving thyroid function. If you’re navigating hypothyroidism or Hashimoto’s, consider exploring your gut health—it might just be the missing link to feeling vibrant again. As always, you should strive to eat whole foods, including animal-based foods with their inherent fats, while avoiding processed grains and seed oils.