Skin Signs of Metabolic Trouble: Acanthosis Nigricans and Beyond

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is a dermatological condition that manifests as darkened, thickened, and often velvety patches of skin. While it can appear in various areas of the body, it most commonly affects skin folds—think the back of the neck, underarms, or groin. At first glance, it might be mistaken for poor hygiene or a simple rash, but its significance runs far deeper. AN is frequently a harbinger of metabolic disturbances, with insulin resistance being the most prominent and well-studied association. To understand this relationship, we need to unpack both the condition itself and the role insulin plays in the body.

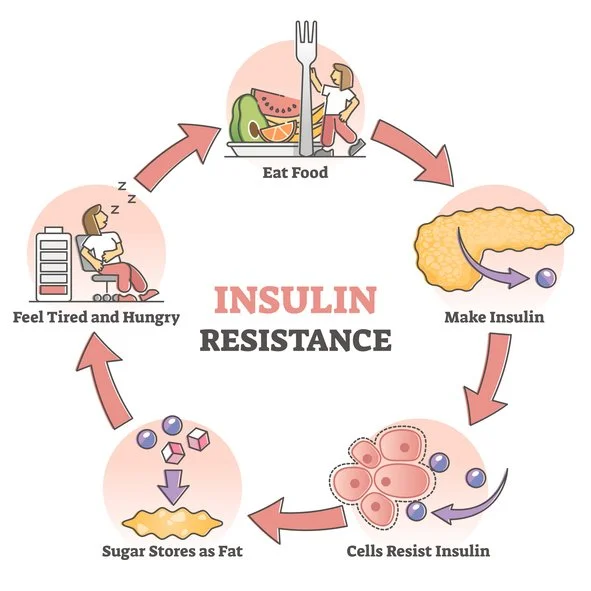

Insulin resistance is a state in which the body's cells become less responsive to insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas that regulates blood sugar by facilitating glucose uptake into cells. When cells resist insulin's signals, the pancreas compensates by producing more insulin, leading to a condition called hyperinsulinemia—elevated insulin levels in the blood. Over time, this can exhaust the pancreas and pave the way for prediabetes or type 2 diabetes. But long before blood sugar levels spiral out of control, the body often sends subtler signals, and acanthosis nigricans is one of them.

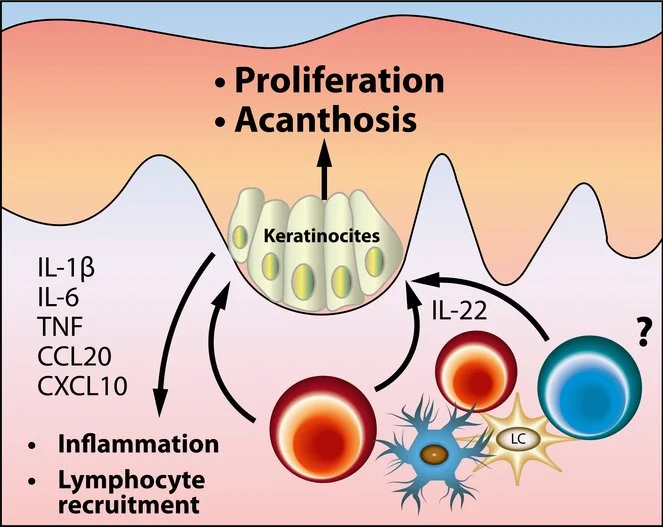

The link between AN and insulin resistance lies in insulin's lesser-known role as a growth factor. At normal levels, insulin primarily manages glucose metabolism. However, in hyperinsulinemia, excess insulin binds to receptors on skin cells, particularly keratinocytes and fibroblasts, stimulating their proliferation. This overgrowth thickens the epidermis and triggers an increase in melanin production, resulting in the characteristic dark, velvety patches of AN. Essentially, the skin becomes a canvas reflecting the body's struggle with insulin overload.

Who develops acanthosis nigricans? While it can occur in anyone, certain risk factors make it more likely. Obesity is a major player, as excess fat tissue—particularly visceral fat—contributes to insulin resistance. Studies show that AN is especially common in individuals with a high body mass index (BMI), with prevalence rates soaring in obese populations. Ethnicity also matters; people of African, Hispanic, or Native American descent are disproportionately affected, possibly due to genetic predispositions to both insulin resistance and AN. Age is another factor—while AN can appear at any life stage, it's increasingly diagnosed in children and adolescents, mirroring the rise in childhood obesity and early-onset metabolic issues.

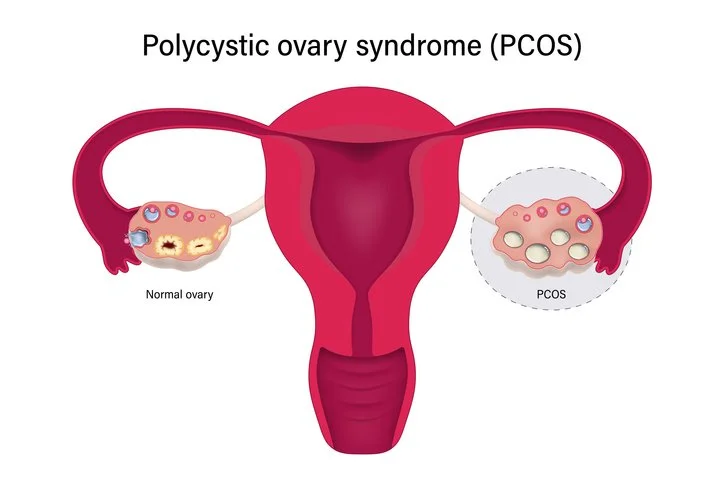

Beyond obesity, AN is tied to other conditions rooted in insulin resistance. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a hormonal disorder affecting women, is a prime example. In PCOS, insulin resistance amplifies androgen production, leading to symptoms like irregular periods, acne, and hirsutism—alongside AN in many cases. Similarly, metabolic syndrome—a cluster of conditions including high blood pressure, elevated blood sugar, and abnormal cholesterol levels—often features AN as a visible marker. Even certain medications, like corticosteroids or oral contraceptives, can induce AN by altering insulin sensitivity, though these cases are less common.

Not all instances of acanthosis nigricans stem from insulin resistance, though. It's worth noting that AN can also arise from rare causes, such as malignancies (e.g., gastric cancer) or genetic disorders. Malignant AN tends to be more sudden, widespread, and severe, often accompanied by weight loss or other systemic symptoms—quite distinct from the gradual onset tied to metabolic issues. For this post, however, we'll focus on the insulin resistance connection, as it's the most prevalent and clinically relevant association.

Diagnosing AN is typically straightforward, relying on visual inspection by a healthcare provider. The darkened, thickened skin is unmistakable once recognized, though it's sometimes confused with conditions like eczema or fungal infections. A biopsy is rarely needed unless the cause is unclear. What's trickier is pinpointing the underlying insulin resistance. Blood tests measuring fasting glucose, HbA1c, or insulin levels can confirm metabolic dysfunction, but AN itself often prompts these investigations in the first place. In this way, the skin acts as an early warning system, flagging issues before they fully manifest in lab results.

So, what does this mean for treatment? Addressing acanthosis nigricans starts with tackling its root cause—insulin resistance. Lifestyle changes are the cornerstone: weight loss, improved diet, and regular exercise can dramatically enhance insulin sensitivity. Losing even 5-10% of body weight has been shown to lighten AN patches and lower diabetes risk. A diet low in refined sugars and processed carbohydrates, paired with aerobic and resistance training, helps restore metabolic balance. In some cases, medications like metformin—a staple in type 2 diabetes management—are prescribed to improve insulin action, often with the added benefit of reducing AN severity.

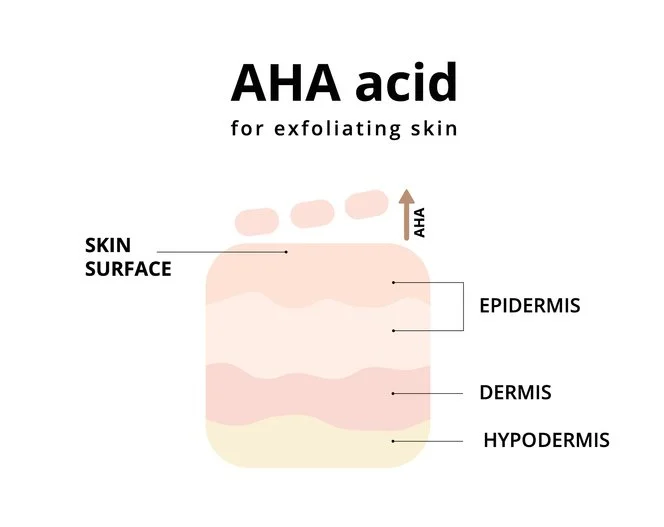

Cosmetically, AN can be stubborn. Topical treatments like retinoids, alpha hydroxy acids, or urea may soften the skin and lighten discoloration, but they don't address the underlying issue. Laser therapy or dermabrasion might appeal to those seeking quicker aesthetic fixes, though these are rarely necessary. The real victory lies in reversing insulin resistance, which not only fades AN but also averts graver health consequences like cardiovascular disease or full-blown diabetes.

The broader implications of this relationship are profound. Acanthosis nigricans is a red flag—a tangible sign of a silent epidemic. With insulin resistance affecting millions worldwide, often undiagnosed until it progresses, AN offers a chance for early intervention. Public health campaigns could leverage its visibility to educate people about metabolic health, especially in at-risk communities. For individuals, spotting those dark patches could prompt a doctor's visit that changes their trajectory.

In conclusion, acanthosis nigricans is far more than a skin quirk—it's a mirror reflecting insulin resistance and its metabolic fallout. By understanding this connection, we can better appreciate the body's intricate signals and act before small warnings become big problems. Whether you're a patient noticing changes or a clinician assessing them, AN is a reminder: what's on the surface often hints at what's brewing beneath.