Winter's Grip: Unraveling the Link Between Solstices, Vitamin D Deficiency, and Deadly Seasonal Illnesses

Yesterday was the shortest day of the year, which means the worst part of the flu season is just ahead. The flu season has long been synonymous with winter's chill, but its timing reveals a deeper connection to the Earth's solar cycle. In the Northern Hemisphere, influenza activity typically ramps up in October, peaks between December and February—shortly after the shortest day of the year on December 21—and tapers off by May, just before the summer solstice on June 21. This pattern isn't a mere coincidence; it mirrors reduced sunlight exposure, crowded indoor environments, and humidity changes that favor viral transmission. Similarly, in the Southern Hemisphere, the flu surges from May to October, cresting in June to August following their winter solstice on June 21, and fading as days lengthen toward December 21. Globally, this creates a perpetual wave: as one hemisphere thaws, the other freezes into vulnerability.

But influenza isn't alone in this solstice-tied rhythm. Many diseases exhibit seasonal spikes during shorter days, contributing to elevated mortality rates in winter months. Respiratory infections like the common cold, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and even COVID-19 variants follow suit, with peaks in colder, darker periods. Beyond viruses, chronic conditions amplify: cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks and strokes, surge in winter due to blood vessel constriction in cold weather and increased clotting risks. Autoimmune flares, acute gout attacks, and even the onset of type 1 diabetes show winter biases, while type 2 diabetes complications worsen with seasonal stress. Measles resurgences tied to dips in post-winter immunity. Overall, winter mortality from all causes can rise by 10-20% in temperate regions, with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases accounting for much of the excess deaths—patterns that ebb as sunlight returns.

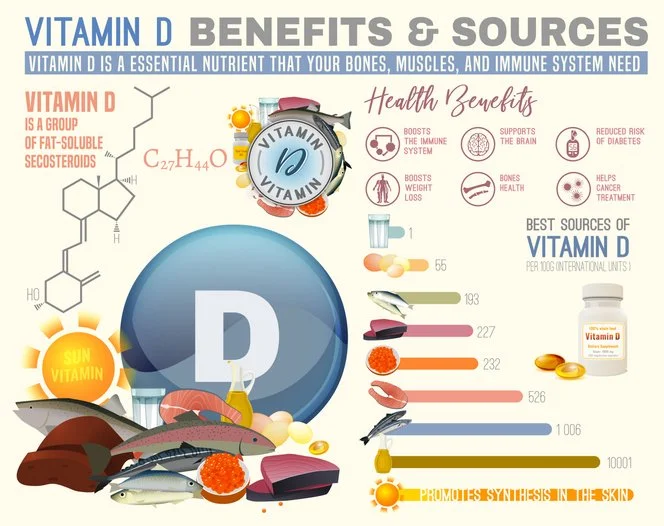

At the heart of these observations lies vitamin D, often dubbed the "sunshine vitamin." Produced in the skin upon UVB exposure, vitamin D levels plummet during shorter days when people spend more time indoors and cover up against the cold. In the U.S., about 35% of adults are deficient in winter, which correlates with an increased risk of infection. Studies show a linear association: those with 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels below 20 ng/mL are more susceptible to flu and respiratory infections, and even have reduced lung function. Vitamin D bolsters innate immunity by enhancing antimicrobial peptides, such as cathelicidin, which disrupt viral envelopes, and modulating adaptive responses to prevent over-inflammation. Randomized trials indicate that supplementation reduces influenza A incidence, especially in groups at risk, such as children or those with inflammatory conditions, which explains why flu vanishes after the summer solstice: rising vitamin D levels from increased sun exposure rebuild defenses, breaking the cycle. For more on vitamin D, sunlight, and health, click on my previous posts here, here, here, and here.

Yet, the story extends beyond prevention to treatment, where heat emerges as a surprising ally. Exposure to warmth—whether through fever, saunas, or thermal therapies—has historical and modern evidence of boosting survival in illnesses. During the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which killed 20-50 million worldwide, aspirin was widely prescribed to lower fever, but high doses (up to 30 grams daily) likely exacerbated mortality. Aspirin toxicity caused fluid buildup in lungs, bleeding, and heart strain, mimicking or worsening viral symptoms—potentially contributing to young adult deaths. Please read my previous post here for more information on heat.

Conversely, allowing or inducing fever through heat treatments showed benefits. Though direct Spanish flu data are sparse, animal studies on influenza reveal that antipyretics such as aspirin increase mortality by 34%, while fever enhances survival. Historical accounts suggest that hydrotherapy, such as hot baths or wraps, improved outcomes by mimicking fever's effects.

Why does heat help? Fever, an ancient evolutionary response, isn't just a symptom—it's a weapon. At 101-104°F (38-40°C), it stresses pathogens: many viruses, like rhinovirus, replicate poorly above body temperature, as seen in studies where warmer nasal passages halt colds. Heat directly inhibits viral enzymes and induces apoptosis in infected cells. For the immune system, fever ramps up metabolism: T cells proliferate faster, produce more cytokines, and migrate efficiently to infection sites. Heat shock proteins (HSPs), triggered by thermal stress, act as chaperones, stabilizing proteins and enhancing antigen presentation to killer cells. Enzymes like RNase L, which degrade viral RNA, are more active at higher temperatures. Inflammation signals, such as IL-6, coordinate responses while thermoregulation aids overall immunity. However, it's a double-edged sword—prolonged fever can cause mitochondrial damage and DNA stress in immune cells, explaining why extreme or unchecked fevers need monitoring.

Modern applications echo this: sauna therapy boosts white blood cell levels, reduces cortisol levels, and cuts respiratory infection risk by up to 50% in regular users. During COVID-19, hyperthermia proposals aimed to inhibit the virus in a similar way. Combining vitamin D optimization—through sun, supplements (2,000-4,000 IU daily for deficient adults)—with mindful heat exposure could mitigate seasonal woes.

In essence, the solstice-driven ebb and flow of diseases underscores nature's balance: darkness breeds vulnerability via vitamin D scarcity, but heat and fever offer a fiery defense. Revisiting the Spanish flu's lessons, we see the peril of suppressing the body's innate tools. As flu seasons loom, perhaps the best prescription is sunlight, a diet high in vitamin D, or supplements, and seeking heat with saunas or exercise.