Plague, Coronavirus, and Beyond: Teeth as a Window to Epidemic History

What happens when archaeology teams up with microbiology? You get paleoproteomics—a cool, modern science that looks at ancient proteins to figure out what germs humans faced long ago. Researchers like Didier Raoult have turned to dental pulp, the soft stuff inside teeth, to find clues about historical diseases. This tissue is special because it holds onto blood and immune markers from when a person died. Two amazing studies show how this works: one spotted Yersinia pestis, the plague bug, in people from the 1700s, and another found traces of a coronavirus in folks from the 1500s. These findings show how paleoproteomics beats the challenges of studying old DNA and helps us understand the sicknesses of the past.

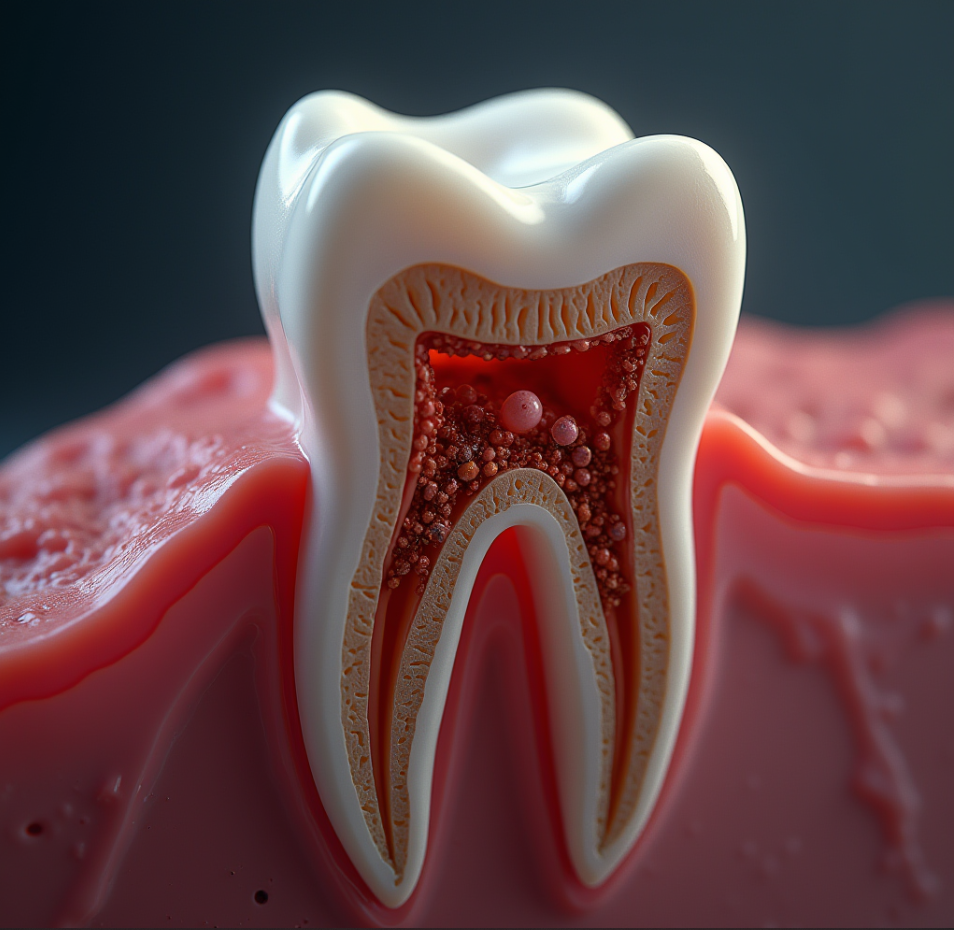

Why dental pulp? It’s like a time capsule. DNA breaks down over time because it’s chemically fragile, but proteins can stick around for hundreds or even thousands of years if conditions are right. Tucked safely inside teeth, the dental pulp keeps a record of what was in someone’s blood when they passed away—think of it as a snapshot of germs and the body’s fight against them. This toughness lets scientists study samples from centuries back, finding infections we’d never spot otherwise. Raoult and his crew use a tool called mass spectrometry to spot peptides—tiny protein pieces—that act like fingerprints of ancient microbes and immune responses.

In a key 2017 study, Rémi Barbieri, Michel Drancourt, and their team checked out the dental pulp from 16 teeth dug up at two spots in France. One was from Martigues (Le Delos), tied to a plague outbreak in 1720–1721, and the other was a plague-free site in Nancy from 1793–1795. They found 650 peptides, narrowing them down to 57 proteins after tossing out stuff like skin flakes (keratin). Of those, 439 peptides came from 30 human proteins, like blood bits (immunoglobulins) and tough tissue (collagen). The big win? In three people from the plague site, four peptides perfectly matched Yersinia pestis proteins—something they didn’t see at the Nancy site. Math backed this up (with a P-value of 0.054), showing it wasn’t just luck, and it matched old records and DNA tests from the same place. Plus, finding immunoglobulins hinted the body was fighting back, suggesting dental pulp can tell us about both the germ and the immune reaction.

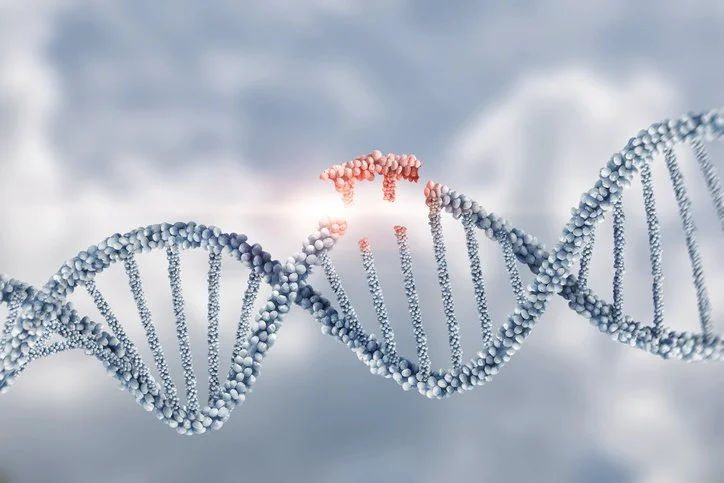

This plague research was built on Raoult’s earlier ideas. Back in the day, his team showed dental pulp could hold DNA from bugs like Y. pestis. But DNA fades fast in old samples, making it tricky to study. Proteins are tougher, so the 2017 study switched gears. Instead of amplifying DNA—which can pick up lab contamination—they used a direct method to spot proteins, which confirmed Y. pestis in 18th-century remains and proved dental pulp could be a treasure trove for paleoproteomics, opening up new possibilities.

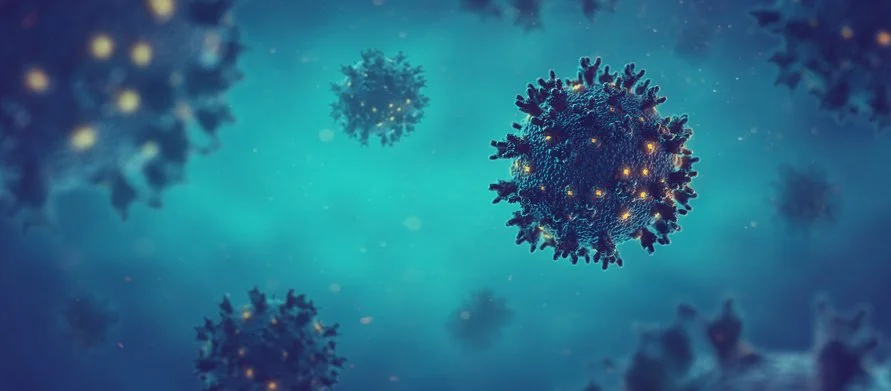

Then, in 2023, Hamadou Oumarou Hama and his team made a jaw-dropping find: signs of an ancient coronavirus in 16th-century France. They dug up 12 skeletons from the Abbey Saint-Pierre in Baume-Les-Messieurs and tested the dental pulp. Using paleoserology (looking for old antibodies) and metaproteomics (studying protein mixes), they found three peptides—36 amino acids total—in two people. These peptides reacted with modern coronaviruses like SARS-CoV-2 and HCoV-229E and tied to viral parts (replicase and nucleocapsid proteins), which suggested a betacoronavirus unlike any we know today, pushing coronavirus history back over 300 years. Dig site clues—like animal bones from pigs, cows, and chickens—hinted it came from animals, a pattern we see with viruses today.

The antibody tests were eye-opening. Blood samples from these two showed strong reactions (over 130,000 units) to SARS-CoV-2, HCoV-229E, and HCoV-OC43, while eight others from the site didn’t. Clean tests with no reactions proved this wasn’t a fluke. The protein data backed it up—only the positive samples had these peptides and signs like proline changes (13.6–15.2%) showed they were truly old. Unlike the plague study, which dealt with a known germ, this one explored a mystery virus with no modern match, making it a bold leap into the unknown.

Both studies show paleoproteomics can do two big things: spot germs and reveal how the body responds. For the plague, immunoglobulins in the pulp pointed to a fight against Y. pestis. For the coronavirus, antibodies plus viral peptides painted a fuller picture. This combo changes how we study old diseases, letting us see not just what killed people but how they battled it. Skipping amplification steps keeps things clean, dodging contamination issues that mess up DNA work.

What does this mean? For the plague, it sharpens our view of past outbreaks, locking in Y. pestis as the 18th-century culprit and setting the stage to track its changes over time. For coronaviruses, it shakes up the idea that they’re new, hinting at animal-to-human jumps way back. The 16th-century animal clues match today’s science, where farms and wildlife spark viral spreads. It’s like COVID-19 might have ancient cousins.

Raoult and his teams are pushing paleoproteomics of the dental pulp, which is a window into history. By cracking open the proteins in old teeth, we get a list of lost germs and proof of human grit. As tools get better and data pile up, this science will dig up more—from the Black Death to vanished viruses—helping us grasp the hidden struggles of our past.

Sources:

Barbieri R, Mekni R, Levasseur A, Chabrière E, Signoli M, Tzortzis S, Aboudharam G, Drancourt M. Paleoproteomics of the Dental Pulp: The plague paradigm. PLoS One. 2017 Jul 26;12(7):e0180552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180552. PMID: 28746380; PMCID: PMC5528255.

Oumarou Hama H, Chenal T, Pible O, Miotello G, Armengaud J, Drancourt M. An ancient coronavirus from individuals in France, circa 16th century. Int J Infect Dis. 2023 Jun;131:7-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2023.03.019. Epub 2023 Mar 15. PMID: 36924840; PMCID: PMC10014125.