The Cognitive Dissonance of Cholesterol and Oreos

Disclaimer: The information contained in this post is not intended to diagnose or treat any condition. It should not be taken as medical advice. If you suspect you have a medical problem, consult with your healthcare provider.

Cognitive dissonance is a psychological phenomenon that occurs when a person holds two contradictory beliefs at the same time. The psychologist Leon Festinger came up with the concept in 1957. Festinger believed that all people are motivated to avoid or resolve cognitive dissonance due to the discomfort it causes, and it can prompt people to adopt certain defense mechanisms when they have to confront it—namely, avoidance, delegitimizing, and limiting the impact. The last thing people seem to want to do is confront the conflicting ideas and change their beliefs. Sadly, scientists are not immune to this phenomenon.

Avoidance involves ignoring or evading dissonance. People may shun situations or individuals that remind them of it, discourage conversation, or distract themselves with busy work. Delegitimizing is the act of undermining evidence of dissonance. It involves discrediting the source that brought attention to the issue. To reduce the discomfort caused by cognitive dissonance, a person may minimize its importance by belittling it, which can be achieved by claiming that the behavior is rare or a one-time occurrence or by presenting rational arguments to convince themselves or others that the behavior is acceptable, thus, limiting the impact. 1

Two Recent Examples

On December 18 and last week, I covered new research on cholesterol, fat intake, and heart disease that may change our perceptions. You can read the posts here and here. I am adding a just-released one today that I will cover later.

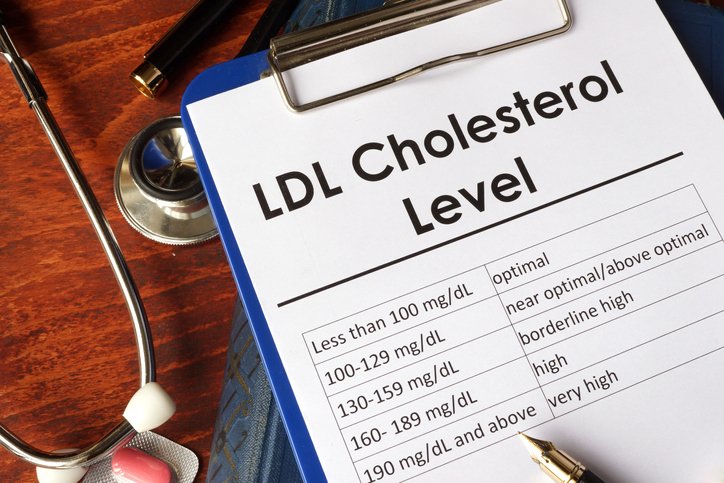

The study I covered on December 18 introduced a subset of lean people on low-carb diets that have very high LDL levels but do not have heart disease. They were named Lean Mass Hyper-responders, and they don’t seem to be at much risk for heart disease. Most people believe high LDL causes heart disease by itself. These people will have a hard time believing that the high LDL the lean mass hyper-responders have won't lead to the development of heart disease. As a result, they may experience cognitive dissonance. They may believe that it is only a matter of time before heart disease sets in for lean mass hyper-responders. They may even dismiss the study and its authors wholesale.

The second study I covered last week showed that thinner people on low-carb, high-fat diets can have skyrocketing LDL levels, whereas those of normal to overweight status have lower LDL, which would seem backward to most people. The crucial finding was that high LDL was much more related to low BMI (thinness)—also, saturated fat intake had a much less dramatic effect than increased BMI. Unbelievable to some, obese people had lower LDL, even though being obese is associated with poor health, heart disease, and diabetes. Again, this seems the opposite of what most people would expect. Faced with the findings, we have a choice; we may ponder whether our old beliefs are flawed or stick to them by ignoring the new information.

My Experience Being a Lean Mass Hyper-responder

I have been a lean mass hyper-responder for almost two decades. I have no other indications of heart disease or poor metabolism. I have zero coronary calcifications by virtue of a few calcium scans, which are the most reliable tests for heart disease risks. The only heart attacks involved with my situation are the ones my original physician had. She wanted me to become a vegan for a year and then retest. Instead, I tested myself one week later, and I had lowered my cholesterol by 25% to near-normal. I never went to her again! Even though recent studies are corroborating new theories, the old literature has never presented much evidence that high cholesterol in otherwise healthy people has ever been an issue. Knowing this, I was able to change my cholesterol level with my diet by adding carbs and seed oils. Knowing what I know now, I would never add seed oils to my diet. Read about their dangers here.

The Explanation For the Obsevations is Called The Lipid Energy Model

The findings from the two studies I just discussed are explained by the new Lipid Energy Model put forth by the researchers. The lipid energy model explains that if fat is being utilized peak efficiently as an energy source, it needs to be packaged in particles (VLDL) that turn into LDL, which has been traditionally deemed to be bad. It also raises HDL, which has been traditionally viewed as a good thing. The two phenomena are seemingly at odds.

The New Evidence Presents Conflicts With the Traditional Cholesterol-Heart Disease Model

Losing weight to achieve a low BMI has traditionally been viewed as a good thing, so how could thin people on low-carb diets have higher LDL? If losing weight is good, why does the LDL rise? These two things can't sit comfortably in the minds of most people who hold to the old diet-heart hypothesis. They will either not believe the data or believe that lean people on low-carb diets will die from heart disease later, even when they show no signs of heart disease today. Or they could rethink their previous beliefs, which most people are not comfortable doing. It is easier to dismiss things and continue with the same beliefs as before.

The Latest Study Using Oreos to Lower Cholesterol

More recently, on January 22, 2024, Nichols Norwitz published a trial that he performed on himself. You can read it here. His experience was that sixteen days of adding twelve Oreo cookies per day lowered his LDL by 71%, and after things went back to the way they were prior to the Oreos (3 months later), he went on six weeks of Rosuvastatin, a cholesterol-lowering statin medication, which only lowered his LDL by 32.5%!

The author is not making a health claim. He is drawing attention to the lipid energy model by inducing a dramatic change with a “bad” diet in which he added 640 calories of pure junk food to intentionally establish tension around the diet-cholesterol theories to stimulate more critical re-examination of them. Nobody thinks Oreos are good for our health, yet they worked twice as well for the subject as the standard of care statin drug Rosuvastatin. Also, Nicholas gained weight eating the Oreos, as one would expect. But gaining weight is bad. But he lowered his cholesterol. The two phenomena are at odds with each other.

Additionally, during this experiment, saturated fat levels increased in the study's Oreo arm; nevertheless, LDL levels decreased, so the results are opposite of what the diet-heart hypothesis predicts because it blames saturated fat for raising cholesterol.

Exercise Seems Bad For Cholesterol Levels, Too

Lastly, in week six, on the statin, Nicholas doubled his activity level, which raised his LDL, refuting the long-held belief that exercise lowers cholesterol, especially LDL. However, the lipid energy model predicts this rise in LDL because the need for more energy stimulates the release of fat from the liver, which, as I discussed before, requires particles (VLDL) that become LDL.

Provoking Thought

All of this is too much to contain in the minds of people who cling to the diet-heart hypothesis. Nicholas is not remotely insinuating that Oreos are good for us or that they should be used to lower LDL in any circumstance. He could have chosen any carbohydrate source. He was trying to show that the Lipid Energy Model predicts lower LDL with the addition of carbohydrates when on a low-carb diet and being a lean mass hyper-responder. I emphasize that Nicholas is a Lean Mass Hyper-responder on a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet. If he had a higher BMI and more carbohydrates in his diet, to begin with, he likely would not have seen the same results. I wonder, had he run the study for a pharmaceutical company, might they have already been patenting Oreos as a new medication to prevent heart disease? Once again, nobody should ever believe that Oreos are healthy or to be used to lower cholesterol.

Based on the Lipid Energy Model, adding carbohydrates to replenish liver glycogen stores will lower LDL. Nicholas decided to be provocative and use Oreos to stimulate thought. His main goal was to demonstrate the prediction of the Lipid Energy Model, which he did. The fact that it is more dramatic than statins serves to establish the strength of the Lipid Energy Model, not to prove that statins don't work or that Oreos should be used instead. He also drew attention to the diet-heart hypothesis and its lack of a reasonable explanation for the observed phenomena.

Without a New Theory, We are Stuck With Too Many Conflicts

Oreos(junk food) were more potent at lowering LDL than statins by far.

Adding saturated fat did not raise cholesterol, as expected, and the weight gain lowered LDL.

Fatter people have lower LDL on low-carbohydrate diets, which does not compute with the diet-heart hypothesis.

Thinner people on low-carb diets can have super-high LDL and not have heart disease, which refutes previous thoughts.

The increased exercise raised LDL while on statins.

The Diet-heart Hypothesis Does Not Explain:

High LDL is expected for lean mass hyper-responders on a low-carb, high-fat diet, and so far, it is not dangerous.

Adding carbohydrates can lead to inflammation while lowering LDL, which can lead to coronary artery disease.

The triad of high HDL, high LDL, and low triglycerides typically found in lean mass hyper-responders does not lead to heart disease, provided they have no other markers like high blood sugar, blood pressure, BMI, etc.

Conclusion

Perhaps the Lipid Energy Model is incorrect, but it explains the observations discussed in this post, whereas the diet-heart hypothesis does not. More research on the lipid energy model and lean mass hyper-responders is forthcoming. In the meantime, we would be well served to look rationally at the science and keep an open mind.