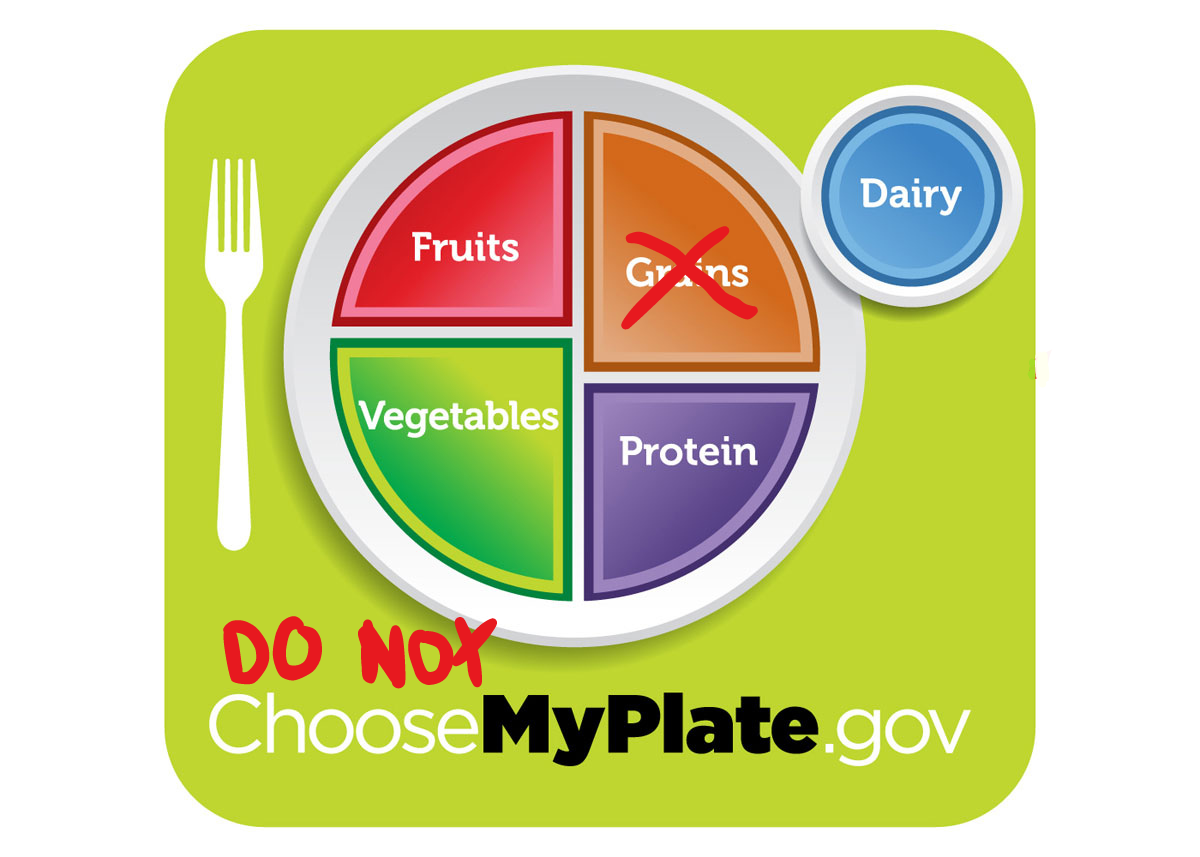

My Plate and The Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Obesity

By now, you may have heard that diets of processed carbohydrates can lead to weight gain. The conventional model states that calories drive weight gain, whether they are from carbs, fat, or protein. The carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity (CIM) posits that processed carbohydrates like bread, bagels, pasta, crackers, chips, and pretzels promote insulin secretion and, therefore, fat storage in adipose (fat cells) tissue, leading to overeating and weight gain. 1 This is one of those chicken-or-egg theories. In the CIM, the diet leads to a situation where the body first wants to store fat, lowering the energy available to burn and leading to the spontaneous desire to eat more calories. Therefore, a diet high in processed carbohydrates, as recommended by MyPlate/My Food Pyramid, may inadvertently contribute to obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, heart disease, and other health issues by disrupting normal metabolic processes and promoting an imbalance in energy intake and storage. Furthermore, the effects linger after diet changes, as determined by a reanalysis of a feeding study I will discuss in this post today.

Below is a diagram of the competing models. The top one reds left to right. The bottom one reads right to left.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6082688/figure/F1/

A new study lends credence to the idea that the traditional dietary guidelines represented by MyPlate/My Food Pyramid, which emphasize a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet, may lead to weight gain and overall poorer health.

The study was a reanalysis of a previously conducted metabolic ward trial involving 20 participants. Although 20 subjects is a bare minimum, metabolic ward feeding studies are considered among the best study designs for nutrition because all of the food is provided by the ward, leading to exact control of what is eaten and more reliable results. The study used a cross-over design with two 2-week diet periods. One group was put on a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet for the first two weeks, followed immediately by a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet without a washout, which is a delay period between the two phases. The other group did the same thing, except they started on the high-carb diet first, followed by the high-fat diet.

The study aimed to investigate the validity of original findings and their implications for the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity. This involved examining the amount of calories consumed for the two different diets and body fat changes between the diets, considering their order and associated metabolic adaptations.

The order of diet, starting with the low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet (LCD) versus a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet (LFD), significantly affected the amount of calories consumed and body fat changes. In the crossover to the high-carb diet, the increase in calorie intake and weight gain was significantly lower.

When the low-carb, high-fat diet was consumed first, participants ate a whopping 1164 fewer calories and had reduced body fat compared to when the low-carb, high-fat diet was consumed second, highlighting a significant carry-over effect from the low-fat, high-carb diet. Conversely, when the high-carb, low-fat diet was consumed first, the participants averaged a significant 924 additional calories. The subsequent low-carb phase resulted in a 41% higher calorie intake and a 26% increase in fat mass. In other words, the tendency to eat less and lose weight was blunted after the high-carb phase. Converting from predominantly burning carbs to burning fat can be a long process, and the effects are often described as the low-carb flu. Conversely, when we are efficient fat-burners, eating processed carbs from time to time will not immediately ruin our ability to primarily burn fat.

The study exposes the limitations of short-term dietary trials without adequate washout periods, suggesting that they fail to capture the long-term effects of dietary changes on metabolism and body composition. It also highlights the metabolic effects of high-carb versus low-carb diets, indicating that many more additional calories are consumed on a high-carb diet, while a low-carb diet leads to calorie deficits of greater than 1000 calories.

The study's findings underscore the importance of considering the long-term metabolic adaptations to dietary changes, especially in the context of macronutrient composition. The USDA dietary guidelines (My Plate) should be re-evaluated in light of these findings. It also suggests that high-fat, low-carb diets (keto, carnivore) should be considered a viable option, with an emphasis on longer-term, more comprehensive studies to understand the true impact of diet on health. I personally believe processed carbohydrates should be avoided as much as is practical. The problem is that grains are inedible unless they are processed, so grain consumption is synonymous with processed carbohydrate consumption in the modern world, even when it is whole-grain.