Light Skin Has Its Origins in Agriculture, Not Northern Migration

The conventional belief that light skin evolved as humans migrated north out of Africa has been widely accepted for many years. However, recent research suggests that the origin of light skin may be more closely tied to the advent of agriculture rather than merely the result of migrating to higher latitudes. This shift in understanding revolves around the crucial role of vitamin D and dietary changes, such as a shift from a diet rich in animal-based foods to one reliant on cereal crops, prompted by agricultural practices.

Vitamin D and Early Human Migration

When early humans left Africa, they carried with them a diet rich in vitamin D, primarily obtained through the consumption of animal products. Vitamin D is essential for calcium absorption and bone health, and the skin can synthesize it upon exposure to sunlight. In Africa, the ample sunlight allowed for sufficient vitamin D production, regardless of dietary intake.

As these early humans migrated north into regions with less sunlight, it is logical to assume that reduced UV exposure would necessitate a physiological adaptation of lighter skin to ensure adequate vitamin D levels. This is because darker skin does not allow UV light to penetrate as easily, and skin exposure to UV light is needed for humans to produce vitamin D. However, isotopic studies of European Neanderthals and early modern humans indicate that both groups were high-level carnivores. This carnivorous diet provided sufficient vitamin D, reducing the immediate pressure to evolve lighter skin solely due to lower sunlight levels.

The Pleistocene Legacy and Light Skin Evolution

Throughout the Pleistocene, a geological epoch characterized by repeated glaciations, human ancestors survived and thrived by hunting large animals, generally called megafauna, which provided a nutrient-dense diet. This diet supported not only physical health but also cognitive development, as the consumption of animal fats and proteins is believed to have played a crucial role in brain evolution. The sudden extinction of these large animals disrupted the established food chains, compelling humans to find alternative food sources.

The transition to agriculture filled this gap but introduced new nutritional challenges. The reliance on cereal crops, which are inherently low in vitamin D, created an environment where light skin provided a distinct survival advantage. This advantage stemmed from the need to synthesize more vitamin D in conditions of limited sunlight and reduced dietary intake.

Isotopic Evidence of Carnivorous Diets

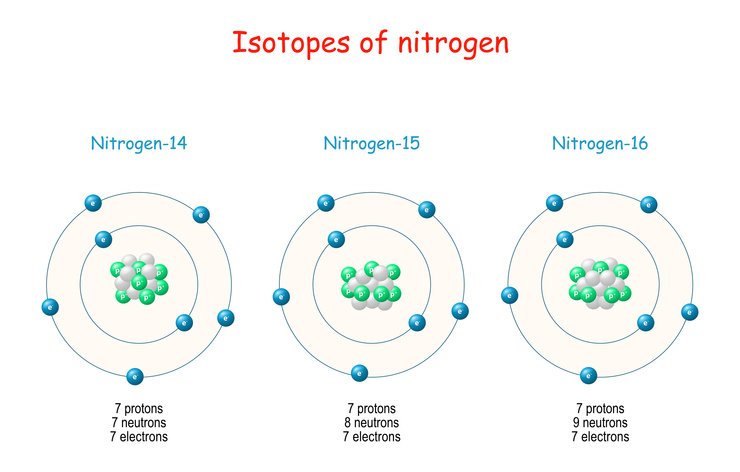

Isotopic analyses of the Nitrogen found in European populations suggest that they were top-level carnivores. The isotopic signatures, which are unique chemical compositions found in the bones, suggest that, during the Pleistocene, both groups consumed large amounts of fatty meat, which would have been a rich source of vitamin D.

This carnivorous diet likely persisted until the extinction of megafauna at the end of the Pleistocene. The loss of these large animals forced humans to adapt their diets, leading to the domestication of plants and animals and the rise of agriculture. The dietary shift, which involved a transition from a diet rich in animal fats and protein to one reliant on domesticated crops, marked a significant change in the availability of essential nutrients, including vitamin D.

The Agricultural Revolution and Dietary Shifts

The real turning point in human evolution came with the advent of agriculture around 10,000 years ago. The transition from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to an agricultural one dramatically altered human diets. Early agricultural societies relied heavily on cereal grains like wheat, barley, and corn, which are poor sources of vitamin D. As a result, populations that depended on these crops faced a significant decrease in dietary vitamin D intake.

Without adequate dietary vitamin D and reduced sun exposure in northern latitudes, these early farmers faced a greater risk of vitamin D deficiency. This deficiency could lead to rickets and other health issues, exerting evolutionary pressure for lighter skin, which is more efficient at producing vitamin D under low UV conditions. Consequently, light skin likely became more prevalent among agricultural populations as an adaptive response to their vitamin D-poor diets. Amazingly, light skin is relatively new in humans.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Evolution of Light Skin

The traditional narrative that light skin evolved primarily due to migration to higher latitudes is being reconsidered in light of new, compelling evidence. While reduced UV exposure in northern regions played a role, the dietary changes brought about by the agricultural revolution appear to have been a more significant driving force. The reliance on vitamin D-poor diets necessitated an adaptation that enhanced vitamin D synthesis, leading to the prevalence of lighter skin in agricultural societies.

Understanding this complex interplay between diet, environment, and physiology provides a more nuanced view of human adaptation and evolution. It highlights the importance of considering multiple factors, including dietary changes and ecological shifts, in shaping our genetic heritage. As we continue to explore the origins of human traits, it is crucial to integrate evidence from various fields to build a comprehensive picture of our evolutionary history.

References:

Allen, B. L., et al. "Why humans kill animals and why we cannot avoid it." Journal of Science of the Total Environment (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165283

Richards MP, Trinkaus E. Out of Africa: modern human origins special feature: isotopic evidence for the diets of European Neanderthals and early modern humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Sep 22;106(38):16034-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903821106. Epub 2009 Aug 11. PMID: 19706482; PMCID: PMC2752538.

Chaplin G, Jablonski NG. The human environment and the vitamin D compromise: Scotland as a case study in human biocultural adaptation and disease susceptibility. Hum Biol. 2013 Aug;85(4):529-52. doi: 10.3378/027.085.0402. PMID: 25019187.