Why Food Calorie Counts Are Misleading: The Truth About Digestion and Nutrients

How Calorie Content Is Measured

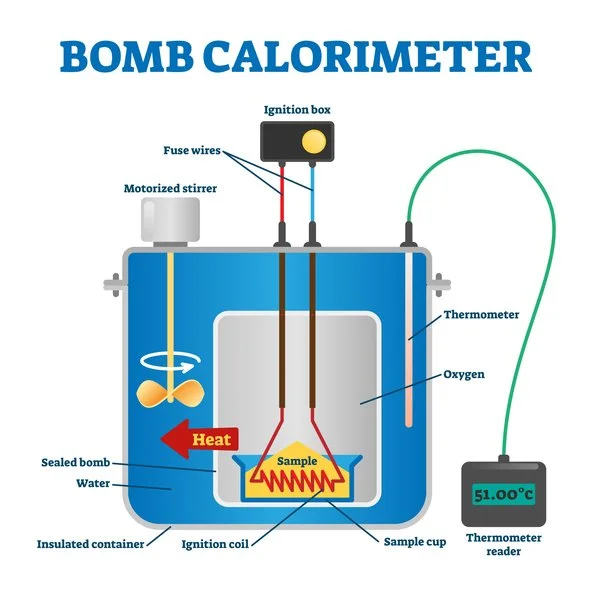

The calorie content listed on food packaging originates from a scientific process that starts with a device called a bomb calorimeter. This tool measures the total energy released when food is completely burned in a controlled environment. Here’s how it works: a small sample of dried food is placed in a sealed chamber filled with oxygen. The food is ignited, and the heat released warms the surrounding water bath. By measuring the temperature change, scientists calculate the energy content in kilocalories (kcal)—the “calories” we see on labels. One calorie is defined as the energy needed to raise the temperature of 1 gram of water by 1°C. However, bomb calorimetry measures gross energy—the maximum energy possible if every component of the food is fully combusted, which isn’t practical for everyday use, so nutritionists rely on the Atwater system to estimate calories based on a food’s macronutrient content:

Carbohydrates: 4 kcal per gram

Proteins: 4 kcal per gram

Fats: 9 kcal per gram

Alcohol: 7 kcal per gram (if applicable)

These values are averages that account for digestion and metabolism, adjusting the gross energy to reflect what the human body typically absorbs. The Atwater system also uses digestibility coefficients to acknowledge that not all food components are fully utilized. For example, carbohydrates are about 90-95% digestible, proteins around 90%, and fats about 95%. Fiber, a type of carbohydrate, is often indigestible, yielding little to no energy.

Why Calorie Counts Are Misleading

The calorie numbers derived from bomb calorimetry and the Atwater system can be misleading because human digestion is far less efficient than a bomb calorimeter. A calorimeter burns everything completely, but our bodies rely on enzymes, gut bacteria, and metabolic pathways that vary in efficiency. Here are the key reasons why:

Incomplete Combustion in the Body

Unlike a bomb calorimeter, which burns food in pure oxygen, our digestive system doesn’t extract all available energy. Factors like gut health, enzyme activity, and even how thoroughly we chew affect how much energy we absorb. For instance, fiber in whole grains or vegetables passes through the digestive tract largely undigested, contributing minimal calories (soluble fiber may yield ~2 kcal/g through gut bacterial fermentation).

Individual Variability

The Atwater system uses generalized digestibility coefficients, but these don’t account for individual differences. Your gut microbiome, digestive health, or even cooking methods can alter how many calories you extract from food. For example, cooking or processing food (like grinding nuts into butter) breaks down cell walls, making more calories available compared to raw or whole foods.

Non-Caloric Nutrients

Not all food components contribute to energy. Micronutrients like vitamins and minerals, such as vitamin A, don’t provide calories because they aren’t burned. Instead, they serve as building blocks or cofactors for essential bodily functions, which we’ll explore later.

Corn and Nuts: A Case Study in Digestion

Certain foods highlight the gap between labeled calories and what your body actually absorbs. Corn and nuts are prime examples due to their structure and composition.

Corn

Corn is rich in carbohydrates, including starch and fiber, but its outer layer (the pericarp) is high in insoluble fiber that resists digestion. If you’ve ever noticed whole corn kernels in your stool, that’s evidence of this. Studies suggest that only about 70-80% of corn’s energy is absorbed, depending on whether it’s eaten whole or processed (e.g., as cornmeal). For example, a 100g serving of corn might be labeled as 90 kcal, but you may absorb only 70-80 kcal due to undigested fiber.

Nuts

Nuts like almonds, walnuts, and pistachios are calorie-dense due to their high fat content (9 kcal/g). However, their tough cell walls trap some fat, preventing full absorption. Research, such as a 2012 study on almonds, shows that the Atwater system overestimates their calories by 20-30%. For instance, 1 ounce of almonds (28g) is labeled as ~160 kcal but may provide only ~120-130 kcal. Processing (e.g., roasting or making nut butter) increases digestibility, narrowing the gap.

These examples show that calorie labels are estimates, not precise values, and foods with high fiber or complex structures deliver fewer usable calories than expected.

Vitamin A: A Nutrient, Not a Fuel

Unlike macronutrients, micronutrients like vitamin A don’t contribute calories because they aren’t metabolized for energy. Instead, they play critical roles in maintaining and rebuilding the body. Vitamin A, found in foods like egg yolks, liver, carrots, and spinach, exists in forms like retinol, retinal, and beta-carotene. Its functions include:

Vision: Retinal is a key component of rhodopsin, a pigment in the retina that supports low-light vision.

Cell Growth: Retinoic acid regulates gene expression, aiding in skin repair, immune function, and tissue development.

Antioxidant Protection: Beta-carotene neutralizes free radicals, protecting cells from damage.

After absorption in the small intestine (aided by dietary fat), vitamin A is stored in the liver or converted into active forms for use in tissues. It’s used in tiny amounts—measured in micrograms, not grams—so it doesn’t contribute to energy balance. For example, the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for vitamin A is ~900 µg RAE for men. Unlike carbohydrates or fats, which are broken down for ATP (energy), vitamin A is a structural or functional component, and excess can be toxic, not stored as energy reserves. Other micronutrients, like B vitamins or calcium, follow a similar pattern: they facilitate metabolic reactions or build tissues without contributing calories. This distinction underscores that food is not just about energy—it’s about providing the raw materials for health.

What This Means for You

Understanding the limitations of calorie counts can change how you approach nutrition. Foods like corn and nuts may provide fewer calories than labeled, especially if eaten whole or minimally processed, which can be a boon for weight management, as high-fiber or structurally complex foods are less calorie-dense than their labels suggest. Meanwhile, nutrients like vitamin A remind us that food’s value extends beyond energy to supporting vision, immunity, and tissue repair. When tracking calories, remember that labels are estimates. Focus on whole foods, and prioritize micronutrient-rich options like eggs, leafy greens, and colorful vegetables to support overall health. If you’re curious about specific foods or nutrients, consider how preparation (e.g., cooking, grinding) affects digestibility and consult a dietitian for personalized advice.