The Power of Skepticism in Navigating Health and Dietary Recommendations

In an era where health and dietary recommendations are constantly evolving, adopting a skeptical mindset can be a powerful tool for making informed decisions about our well-being. From government-backed dietary guidelines like MyPlate and the Food Pyramid to pharmaceutical claims of life-changing benefits, many widely accepted recommendations have later been questioned or debunked. By approaching health advice with critical thinking, we can avoid being swayed by dogma, misleading statistics, or unproven interventions. This post explores why skepticism is beneficial, using examples like MyPlate, the EAT-Lancet diet, pharmaceutical relative risk reduction tactics, and flawed medical recommendations such as spinal fusion. It also emphasizes the importance of personal research, humility, and openness to being wrong in the pursuit of better health choices.

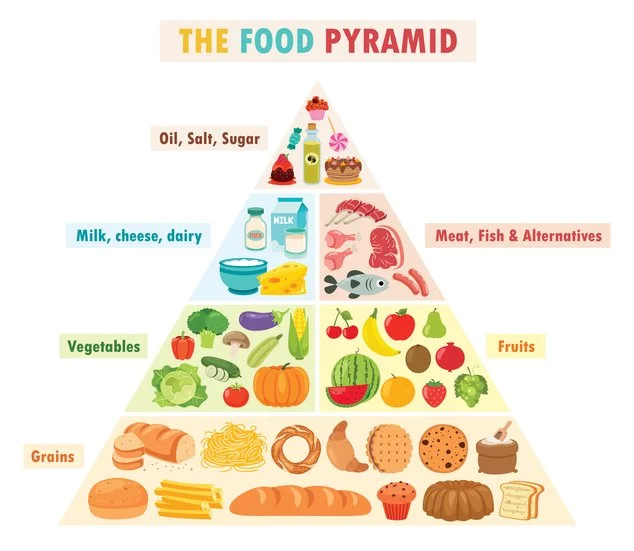

The Fallacy of Dietary Guidelines: MyPlate and the Food Pyramid

For decades, the U.S. government’s dietary guidelines, embodied in the Food Pyramid (introduced in 1992) and later MyPlate (2011), were presented as the gold standard for healthy eating. The Food Pyramid emphasized a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet, with 6–11 daily servings of grains and minimal fats. MyPlate, while more visually streamlined, continued to promote a carbohydrate-heavy diet with a focus on grains and low-fat dairy, whose recommendations were backed by authoritative institutions like the USDA, yet they have faced significant criticism for their lack of robust evidence and potential contribution to obesity and chronic disease. Skeptics who questioned the Food Pyramid’s one-size-fits-all approach were often dismissed as fringe, yet emerging research has supported their concerns. Studies, such as those published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2018), have linked high-carbohydrate diets to increased risks of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, challenging the low-fat dogma. The influence of food industry lobbying on these guidelines, particularly from grain and sugar producers, further muddies the waters. A skeptic might ask: If these guidelines were truly evidence-based, why have obesity rates in the U.S. risen from 13% in the 1960s to over 40% today, despite widespread adherence to these recommendations ? Similarly, the EAT-Lancet diet, launched in 2019, promotes a “planetary health diet” heavy on plant-based foods and low in red meat and animal fats. Touted as a solution to both human health and environmental sustainability, it claims to reduce premature deaths by 11 million annually. However, skeptics have pointed out flaws in its one-size-fits-all approach. The diet’s reliance on observational studies, which cannot prove causation, and its dismissal of nutrient-dense animal foods like eggs or liver, raise red flags. For instance, a 2020 study in Frontiers in Nutrition argued that the EAT-Lancet diet may lead to nutrient deficiencies, particularly in vitamin B12 and iron, for certain populations. A skeptical approach—questioning the universal applicability of such diets and seeking out primary research—can prevent individuals from blindly adopting potentially suboptimal dietary patterns.

Pharmaceutical Misrepresentation: The Trap of Relative Risk Reduction

Pharmaceutical companies often use relative risk reduction (RRR) to exaggerate the benefits of their drugs, a tactic that skeptics can learn to spot. Take statins, widely prescribed to lower cholesterol and reduce heart disease risk. A 2005 study in The Lancet reported that statins reduced the relative risk of major cardiovascular events by 20–30%, which sounds impressive, but the absolute risk reduction (ARR) tells a different story. For example, if the baseline risk of a heart attack is 2% over five years, a 25% RRR means the risk drops to 1.5%—an ARR of just 0.5%. For every 200 people treated, only one might avoid a heart attack, while others face side effects like muscle pain or diabetes risk (noted in a 2011 JAMA study). A skeptic would dig into the numbers, questioning whether the benefits justify the risks for their health profile.

Bisphosphonates, used for osteoporosis, follow a similar pattern. A 1998 study in The New England Journal of Medicine claimed a 50% RRR in hip fractures for women taking alendronate. However, the ARR was only about 1% over three years, meaning 100 women would need to be treated to prevent one fracture, while side effects like esophageal irritation or rare jaw osteonecrosis could affect others. Skeptics who scrutinize these statistics are better equipped to weigh the true benefits against potential harms. The case of Vioxx, a painkiller withdrawn in 2004, underscores the dangers of uncritical acceptance.

Marketed as a safer alternative to older NSAIDs, Vioxx was linked to a 2005 NEJM study showing it doubled the risk of heart attacks and strokes. Patients who questioned its necessity or opted for non-pharmacological pain management avoided these risks. Skepticism, in this case, could have been lifesaving.

Flawed Medical Recommendations: Spinal Fusion and Cholesterol Myths

Medical interventions like spinal fusion for chronic back pain have been heavily promoted, yet skepticism has revealed their limitations. A 2019 The Lancet series on low back pain concluded that spinal fusion, often costing tens of thousands of dollars, offers no significant benefit over conservative treatments like physical therapy for most patients. Complications, including infection or failed surgeries, occur in up to 20% of cases, per a 2016 Spine journal study. A skeptic who researches alternatives, such as exercise or cognitive behavioral therapy, might avoid unnecessary surgery and its risks. The outdated view that dietary cholesterol directly causes heart disease is another example of dogma that skepticism has helped dismantle. For decades, eggs were vilified based on observational data linking cholesterol intake to heart disease. However, randomized controlled trials, like those summarized in a 2013 American Journal of Clinical Nutrition meta-analysis, found no significant link between dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular events in most populations. The 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans finally dropped cholesterol restrictions, validating skeptics who questioned earlier recommendations.

The Danger of Dogmatic Thinking

Dogmatic thinking—blindly accepting expert advice—can stifle exploration of viable health options. For example, the low-fat dogma sidelined ketogenic and low-carb diets, which have shown promise for weight loss and metabolic health in studies like a 2018 The Lancet trial. Similarly, the dismissal of fasting or time-restricted eating as “fad diets” ignored evidence, such as a 2020 Cell Metabolism study, showing benefits for insulin sensitivity. A skeptic who questions mainstream narratives and seeks out primary research can uncover these alternatives, tailoring choices to their unique needs.

The Value of Personal Research and Humility

Doing our research, while daunting, empowers us to make better health decisions. PubMed, Google Scholar, or even reputable science-based blogs can provide access to primary studies, bypassing filtered media reports. For example, a skeptic researching statins might find a 2016 BMJ article highlighting overprescription in low-risk patients, prompting a discussion with their doctor about lifestyle changes instead. While we may not become experts, building a knowledge base over time fosters confidence in decision-making. However, skepticism must be paired with humility. No one knows everything, and clinging to a belief despite contradictory evidence can be as harmful as blind acceptance. Admitting when we’re wrong—whether about a diet, supplement, or treatment—allows us to adapt and grow. For instance, someone who initially embraced the Food Pyramid might, upon reviewing newer evidence, shift to a more balanced diet with healthy fats, acknowledging their earlier misstep.

Conclusion: Skepticism and Humility as a Winning Combination

A healthy dose of skepticism, coupled with a humble acknowledgment that there’s always more to learn, is a powerful approach to health and dietary choices. By questioning guidelines like MyPlate or EAT-Lancet, scrutinizing pharmaceutical claims, and reevaluating medical interventions like spinal fusion, we can avoid pitfalls and tailor decisions to our needs. While personal research may not make us experts, it equips us to navigate the complex landscape of health advice. Staying open to new evidence and willing to admit when we’re wrong ensures we remain adaptable in our pursuit of well-being. In a world of ever-shifting recommendations, skepticism and humility are not just beneficial—they’re essential.